Solzhenitsyn: a life of dissent

Monday 04 August 2008

Latest in Europe

From the blogs

Railways are too important to run on greed

In the novel Catch 22, one of the central characters is an entrepreneurial war profiteer by the name...

“The Football Crash”: Are footballers the bankers of modern sport?

For some time now, the headlines about footballers’ wages have seemed oddly familiar; and, with the ...

Why bother changing the GCSEs?

If you wish to change something, abolish exams completely, instead of making them more stressful for...

Is this the real life, or is this just Twitter?

It seems not a week goes by without some news story involving Twitter abuse, just last week we had n...

Related articles

When Alexander Solzhenitsyn's 'One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich' appeared in the thick monthly literary magazine Novy Mir back in November of 1962, taboos were shattered. Buried secrets were unearthed. And the Soviet Union was shaken to its foundations.

Solzhenitsyn's short novel described a single day in the life of a carpenter caught up in the Soviet Union's secret network of slave labor camps, where starvation, bitter cold and punishing work regimes were the rule and, it has been said, the average life expectancy was one winter.

The author was working as a provincial math teacher, and his greatest work, "The Gulag Archipelago," was still to come. But "One Day" was to shock the USSR and the world.

Some of the crimes of the dictator Josef Stalin were exposed and denounced following a secret speech by Communist Party leader Nikita Khrushchev in 1956, as part of his short-lived campaign to reform the brutal Soviet system.

But Solzhenitsyn's novel, based on the seven years he spent as a prisoner, was the first real expose of the gulag — a word derived from the Russian "Glavnoe Upravelenie Lagerei," or Main Camp Administration.

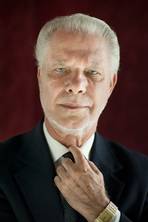

Solzhenitsyn, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature but was exiled from his homeland because of his work, died of heart failure yesterday at age 89, his son Stepan Solzhenitsyn told The Associated Press.

The gulag was, Solzhenitsyn wrote, the "human meat grinder" for processing what Stalin sneered at as "wreckers," vermin and "enemies of the people" who allegedly sabotaged Soviet progress to the workers' paradise. The grim process started, typically, with a knock on the door late at night, an arrest on charges of trivial or imaginary crimes, condemnation by a secret tribunal, transportation by unheated rail car and finally incarceration in the camps.

The prisoners formed a secret army of slave laborers who built railroads, worked in mines and cleared forests in some of the world's most inhospitable terrain. In the end, by the most authoritative estimate, the gulag systematically ground down some 29 million souls.

Armed with his literary talent and prodigious memory, Solzhenitsyn spent more than 40 years working in secrecy, in fear and finally in exile as he chiseled away at the lies that supported the Soviet system. And in the end he, as much perhaps as any individual, helped to bring it down.

'One Day' was the critical beginning of this work.

"If the Soviet Union's elite were to accept that the portrait of Ivan Denisovich was authentic, that meant admitting that innocent people had endured pointless suffering," wrote Anne Applebaum in her book, 'Gulag: A History'. "If the camps had really been stupid and wasteful and tragic, that meant that the Soviet Union was stupid and wasteful and tragic too."

After the book appeared, readers of Novyi Mir responded with an outpouring of letters describing their anguish and grief. "Now I read and weep, but when I was imprisoned in Ukhta for ten years I did not shed a tear," one reader said in letter to the magazine.

Solzhenitsyn's novel would never have been published if Khrushchev hadn't hoped it would undermine support in the Kremlin for neo-Stalinist policies. But perhaps in part because of the novel's publication, Khrushchev was ousted by Communist Party leaders in 1964. The gulag, meanwhile, continued to incarcerate enemies of the people until two years before the Soviet collapse.

When Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel Prize in 1970, Soviet authorities refused to let him go to Stockholm to accept the award. In the text of the speech he could not deliver to the Swedish Academy, smuggled out of the USSR, Solzhenitsyn recalled an old Russian proverb: "One word of truth shall outweigh the whole world."

But Solzhenitsyn was not a storybook hero for his admirers in Europe and the United States. Many, especially in the West, found his political judgments as distressing as his literature was inspiring.

After he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship and expelled from the USSR in 1974, he settled in bucolic Cavendish, Vermont. There, he became frustrated with what he regarded as the West's shallow obsession with individualism and liberty — which, in his view, had degenerated into narcissism and license. Democracy had brought paralysis, he believed, affluence decadence.

In a 1978 speech at Harvard University, Solzhenitsyn — who with his beard and dour demeanor resembled a figure from an Orthodox icon — denounced the Western view that liberal democracy was fated to triumph in non-Western civilizations, which he called "worlds" unto themselves.

"There is this belief that all those other worlds are only being temporarily prevented by wicked governments or by heavy crises or by their own barbarity or incomprehension from taking the way of Western pluralistic democracy and from adopting the Western way of life," Solzhenitsyn said.

"It is a soothing theory which overlooks the fact that these worlds are not at all developing into similarity; neither one can be transformed into the other without the use of violence."

After his return to Russia in 1994, Solzhenitsyn was outraged by what he found — a Kremlin, in his view, unable to stop the looting of Russia's vast resources by politically connected tycoons and unwilling to stand up against what he saw as the encroaching threat of NATO and other Western institutions.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the Communist reformer, restored Solzhenitsyn's Soviet citizenship in 1990 and dropped treason charges against him. President Boris Yeltsin, who dismantled the Soviet system, tried to woo the author.

Solzhenitsyn blamed Gorbachev and Yeltsin for Russia's economic crisis, its military weakness and what he regarded as subservience to the West.

When Yeltsin awarded Solzhenitsyn Russia's highest honor, the Order of St Andrew, in 1998 the writer refused to accept it. When Yeltsin left office in 2000, Solzhenitsyn wanted him prosecuted.

"I feel that Yeltsin permitted an enormous devastation of Russia," Solzhenitsyn told the New Yorker's David Remnick in 2001.

In the 1990s, Solzhenitsyn's views were regarded by Moscow's political elites and some disillusioned Western supporters as old-fashioned, out of step with Russia's march toward integration with the West. In time, however, Solzhenitsyn's views would be echoed in the halls of the Kremlin.

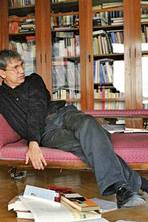

The author at first seemed wary of President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer. But he gradually warmed to Putin, as the Russian president reigned in the oligarchs, reclaimed state control of some of Russia's natural resources and adopted a more assertive — at times confrontational — relationship with the United States and the West.

Solzhenitsyn, meanwhile, did not quarrel with the Kremlin's drive to eliminate voices of dissent from the media, marginalize the political opposition and restore its role as the unchallenged center of Russian power.

Russian liberals are careful to draw the distinction between Solzhenitsyn the writer and Solzhenitsyn the political figure. They cherish the former, and are reluctant to criticize the latter.

"He wrote the 'Gulag Archipelago'," Andre Mironov, who was sentenced to a term in a prison camp in the 1980s for possession of unauthorized books, told The Associated Press. "This was above all."

Some Western critics, meanwhile, have been harsher, accusing Solzhenitsyn of becoming an apologist for Putin's authoritarian rule.

Last year, after three years in relative obscurity, Solzhenitsyn granted a rare interview to the liberal weekly Moscow News, in which he warned that Russia risked a Ukrainian-style revolt because of Western interference. He also accused the United States of the "occupation" of Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Putin's assertive foreign policy, he was quoted as saying, was "forward thinking," while blaming the Russian president's predecessors for the gulf separating Russia's ultra-wealthy elites and its millions of poor.

On June 12, during the Day of Russia holiday celebrations in the Kremlin, Putin presented Solzhenitsyn with a state prize for his "humanitarian" contribution to the nation. The author, apparently too frail to attend, was represented by his wife, Natalya.

"Millions of people associate the name and work of Alexander Solzhenitsyn with Russia's fate," Putin said at the ceremony. "His academic research, outstanding literary work and, in fact, his entire life have been dedicated to the Fatherland."

In a taped message, Solzhenitsyn said he hoped Russians' experience during the "cruel and troubled years" of the Soviet era would help avert more suffering. "It will forewarn and protect us from destructive breakdowns," he said, looking pale and thin in a gray suit and tie.

Solzhenitsyn had become, once again, a symbol of Russia: a nation caught between its tragic past and its uncertain future; between its faith in state power and its fear of new repression.

His journey was, after all, Russia's bitter journey through the 20th century. And if the West sometimes had a hard time understanding Solzhenitsyn and his country, well, perhaps that's because of Russia's singular history.

"How can you expect a man who is warm to understand a man who is cold?" he wrote in 'One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch.'

- 1 Pippa Bartolotti: 'Yes I drive a Jaguar – but why should that stop me leading the Green Party?'

- 2 US 'should hand over footage of drone strikes or face UN inquiry'

- 3 Isabelle Caro, the face of anorexia, dies at 28

- 4 Burma's Rohingya Muslims: Aung San Suu Kyi's blind spot

- 5 Barf a minute: After Lady Gaga pukes mid-performance we round-up some other on-stage 'oops' moments

- 6 Tony Scott death: Top Gun director dies after jumping from Los Angeles bridge

- 7 Ten adverts that shocked the world

- 8 News in pictures

- 9 Is Helen Mirren right about date rape?

- 10 Charities accuse Rihanna of 'sanctioning' violence

- 1 US 'should hand over footage of drone strikes or face UN inquiry'

493 comments | 0 minutes ago

- 2 Government U-turn 'will deny council housing to millions'

210 comments | 16 minutes ago

- 3 Pippa Bartolotti: 'Yes I drive a Jaguar – but why should that stop me leading the Green Party?'

210 comments | 0 minutes ago

- 4 Iain Duncan Smith attacks BBC for 'peeing all over British industry'

335 comments | 2 minutes ago

- 5 Hague ignored lawyers to send Assange 'threat' note

372 comments | 12 minutes ago

- 1 Pippa Bartolotti: 'Yes I drive a Jaguar – but why should that stop me leading the Green Party?'

- 2 Twitterers clarify rumours of Jackie Chan's death

- 3 First she lost her boyfriend Robert Pattinson, now Kristen Stewart has lost her big part

- 4 Isabelle Caro, the face of anorexia, dies at 28

- 5 A-Level Results: Britain's top pupil rejects Oxbridge

- 6 Harry Potter's secret is out after PR slip gives the game away

- 7 ‘Devastated’ Ennis falls victim to gold robbery

- 8 Is Helen Mirren right about date rape?

- 9 Asexuals – the fourth sexual orientation

- 10 QPR captain Joey Barton threatens to 'expose' Gary Lineker and says of Match of the Day pundit Alan Shearer - 'I despise him'

Recently Read

HelpUnshare A new social reading experience from The Independent, powered by Facebook. Learn More

- This article wasn't posted to Facebook because you've read it previously

- Ten adverts that shocked the world

Unshare4 days ago

Business videos from commercial thought leaders

Watch the best in the business world give their insights into the world of business.

Experience the Heineken Hub

Get free wi-fi and exclusive i content while you enjoy a tasty pint of Heineken at participating pubs.

Win a guided tour of Superhuman

With dinner for two and a £50 book token for the intriguing exhibition at the Wellcome Collection.

Win your very own tailor-made holiday to Switzerland

Whether you'd rather hike up a mountain or relax in a spa, you'll love this trip to Graubünden.

A legacy we can be proud of

The most lasting effect London 2012 will have is to motivate children all over the UK to get interested in science, technology, engineering and maths

Looking to make extra cash this summer?

London will be busy this summer, so why not rent your house, flat or spare room with Airbnb?

Now showing at the O2

Check out the cool stuff happening under our tent: the hottest gigs, comedy, sport, films, clubs, bars, restaurants and much more.

Enter the latest Independent competitions

Win anything from gadgets to five-star holidays on our competitions and offers page.

Business videos from commercial thought leaders

Watch the best in the business world give their insights into the world of business.

Experience the Heineken Hub

Get free wi-fi and exclusive i content while you enjoy a tasty pint of Heineken at participating pubs.

Comments